- Home

- Andrew J. Fenady

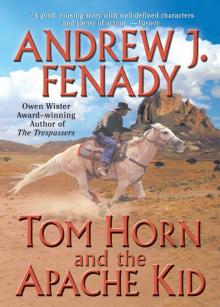

Tom Horn And The Apache Kid

Tom Horn And The Apache Kid Read online

Tom Horn and the Apache Kid

Andrew J. Fenady

LEISURE BOOKS NEW YORK CITY

For John Wayne,

who knew and

loved the West

And Mary Frances,

who came with

me to see

the elephant

The Eagle

He clasps the crag with crooked hands;

Close to the sun in lonely lands,

Ringed with the azure world, he stands.

The wrinkled span beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

The Eagle

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Other Leisure books by Andrew J. Fenady

Copyright

Chapter One

The dawning sun jutted above the jagged mountain rim and flared into the big man’s eyes, distorting his vision. His gnarled hand rubbed across his face. He blinked, squinted, and took another look toward the distant camp composed of two wickiups backed against the Rincon Range.

There was no visible sign of life, only dawn sounds, crickets and the chirps and chattering of hungry birds.

Al Sieber, chief of scouts, started to crawl forward. He was in his late fifties now, used up and juiced out. But enough of the old agility and a lot of the strength remained. Sieber had taken part in more Indian fights than Daniel Boone, Jim Bridger, and Kit Carson combined. His body had collected twenty-nine wounds.

Suddenly Sieber stiffened and froze. The bird noises had ceased.

A rifle barrel dipped and pointedjust inches from the old scout’s head. Sieber looked up the narrow, deadly rifle barrel to the man holding the Winchester. The man, dressed in a buckskin shirt and blanched brown pants, stretched up more than six feet, but from Sieber’s position he looked about ten feet tall.

“Morning, Al.” Tom Horn stood smiling out of a handsome catgut face with calm, silver blue eyes.

“Tom, you do know how to set up camp.”

“Had a good teacher.”

“Teacher needs to talk to you.”

“Had breakfast, Al?”

“Yesterday.”

“Well, let’s have some breakfast and talk.” Horn extended the butt of the Winchester to help Sieber. “How’s the rheumatism?”

“Kicking up.”

Tom Horn was a speck somewhere inthe vast patchwork of Apachedom and Al Sieber had found him. But then Tom Horn had also found Al Sieber. For nearly a de cade, the gruff, taciturn chief of scouts had been tutoring Tom Horn in the fine and bloody art of scouting and staying alive; now the two men nearly thought in tandem.

Part of it was inborn in Horn. Not everyone could be taught the rudiments of scouting. Not one in ten, or ahundred, or even a thousand. Not if the hunter’s instinct was not there to begin with. That instinct was a part of Horn’s mind and body. His eyes were made for the unseen trail and his hand for the trigger. But good eyes didn’t necessarily make a good scout, and a single accurate shot didn’t necessarily keepyou alive inthe warring world of Apacheria.

Sieber had honed Horn’s natural abilities and perceptions. He had taught his eagerpupil to accumulate and evaluate what had happened, what was happening, and what to do about it—with accuracy and alacrity. The two had saved each other’s lives as casually as other men played cards.

Moreoften than not, thestakesin the game Sieber and Horn played were life and death. The arena was nature’s arrant, cruel cathedral—the Arizona Territory: five hundred thousand square miles bordered on the north by the Colorado River, curving west to the California frontier, east toward the Dragoons and south along the Rio Grande and the Mexican border.

But the marauding Apaches were no respecters of borders. Again and again they crossed into Mexico to escape pursuing troopers and to wreak havoc on the Mexicans, whom they despised and disdained. And there, ensconced in their phantom-like rancherías, the Apaches waited and mated until the time came to move to the north again and strike at the uncountable whites who had claimed and “civilized” the once proud Apache empire.

An Apache chief could accord a warrior no higher accolade than to grant him the title of eagle as part of his name. Of all living things, the Apache held the golden eagle in the greatest respect and reverence. The golden eagle embodied those attributes whichthe Apaches considered supreme: courage, vigilance, swiftness, and independence.

When an Apache chief perceived all these elements commingled in abrave,that brave was granted the honor of attaching the title of eagle to a descriptive word as part of his name: Soaring Eagle, Searching Eagle, Racing Eagle, Warring Eagle, and Dancing Eagle.

When Cochise, one of the bravest, wisest, most respected Chiricahua chiefs, made peace with Al Sieber after many fierce encounters, he took the chief of scouts as his blood brother. During that ceremony Cochise bestowed the highest possible honor on his former adversary. From that time on, Al Sieber’s Indian name would be the Eagle—no other descriptive word. The purest, the highest,— the Eagle.

And now the Eagle had sought out Horn again. Once again each man knew the stakes would be life and death.

The wickiup was a rude framework of saplings covered with hides and brush. It had one entrance, facing east. There was a small fire in the center of a little scooped-out place. Horn and Sieber sat and ate while Suwan fed the hungry baby from her milk-filled breast.

The Indian woman could not have been more than twenty. She was copper-colored, with fawn-like eyes set wide apart and with long lashes and narrow eyebrows for an Apache.

“You weren’t easy to find,” Sieber said.

“How long you been looking, Al?”

“Ten sleeps. You winter here?”

“Yep.”

“That your papoose?”

“Was a cold winter.”

“Uh huh.”

If Suwan understood she gave no indication of it.

“What you doing this side of the Rincon, Al?”

“General Crook sent me to fetch you. He’s getting up an expedition.”

“What for?”

“For Goklaya.”

“Again?” Horn chewed on a tender piece of fowl. “Crook’ll just chase that old panther to the border, then have to turn back.”

“Not this time.” Sieber wiped at his mouth with the worn edge of his sleeve. “The general’s worked out a deal with the Meskins, some kind of ‘hot-trail treaty.’ He’s going in. Wants Tom Horn to go with him. Two-hundred-dollar

bonus, one hundred twenty-five a month.”

“Starting when?”

“Starting now.”

Horn looked at Sieber. “Let’s start.”

Both men rose. Sieber looked atSuwan.The baby had fallen asleep against Suwan’s exposed breasts. She gazed at the child with the slightest trace of a smile on her generous red lips.

“Good-looking squaw,” said Sieber.

“Yep.” Horn nodded without glancing at Suwan. “Maybe I’ll winter with her again next year.”

A rope-thin old Indian walked out of the second, smaller wickiup but paid Horn and Sieber no attention as the scouts mounted up.

“What about your otherhorses and possibles?” Sieber asked.

“Ought to leave ol’ Pedro and his granddaughter something…besides that papoose.”

“I reckon,” Sieber agreed. They started to ride. “We got to make one more stop.”

“Calculated we would.” Horn pulled down on the brim of his hat and patted the mane of Pilgrim, his sure-footed buckskin.

The two men rode all day and into the night, as they had done many times. They rode in silence, with only their horses’ hoofbeats serenading the soft, wind-chased sand.

To many, especially strangers, Sieber seemed a somber man, a man of few words and dark and murky moods. But the white and red scouts who served under him respected him—and feared him. Sieber never ordered his scouts to do anything he hadn’t done and wouldn’t do again. He was a man of justice—but sometimes justice had to be cruel.

Horn had witnessed many acts of kindness and compassion on Sieber’s part, acts Sieber did his best to camouflage. He was a man of perplexing paradoxes—quiet, inert, passive one moment, a lightning bolt of fury the next. One time Horn watched as Sieber twice quietly warned a renegade Apache to cease brewing the forbidden tizwin. The third time the Indian went for a weapon, Sieber decapitated the hapless red man with one swift stroke of a Bowie knife.

Sieber was not one to speak of his beginnings, but bit by bit, through countless campfires and whiskey bottles, Horn had pieced together the tapestry of his mentor’s life.

Sieber was born along the upper Rhine in Germany on the leap year day of February 29, 1844, one of seven children with a father soon dead. His mother and brood emigrated to the United States and settled in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, near Conestoga Creek, then moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1856. As a boy, Al hunted and trapped. During the Civil War when barely eighteen, he enlisted in the First Minnesota Volunteers, a well-blooded outfit. He fought at the Battle of Fair Oaks, at Antietam and Fredericksburg, and the following spring at Chancellorsville. By then young Sieber was the crack marksman in his regiment. He served with valor at the second Battle of Bull Run and at Gettysburg, where he was wounded in the head and the leg.

Sergeant Sieber convalesced at York, Pennsylvania, and mustered out of the Yankee army with several scars and three hundred dollars. In 1866, civilian Sieber headed west to San Francisco and went to work on the Central Pacific. Later he herded horses from California to Prescott, Arizona, where he came under the tutelage of an army scout named Dan O’Leary.

From that time on, Al Sieber’s experience and reputation as a scout, hunter, and marksman swelled to legendary proportions.

Now, once again, Tom Horn was riding with that legend—Al Sieber, the Eagle.

An hour after sundown the two men reined in their weary animals. Through the damp darkness Horn could barely make out the sign at the crossroad: “VALVERDE 5 miles, West” and “COLD-IRON 10 miles, East.”

“Valverde, five miles,” read Horn.

“Then Rosa’s hen house is just down the road a piece,” said Sieber.

Within ten minutes Horn and Sieber arrived at the isolated two-story wooden building. They dismounted, tied off their animals, and walked onto the porch. There were lights inside. Horn tried the door, then knocked. No answer. He knocked again. Finally a coarse female voice answered.

“We’re closed up.”

Horn banged on the door harder.

“Go away. We’re closed up!” The voice responded louder. Horn looked at Sieber, shrugged, then kicked the door in. Both men barged through the shattered door into the parlor and surveyed the surroundings.

Several señoritas of assorted hues, sizes, and states of undress were present. There was a bar, fashioned of planks nailed on barrels. A heavy stairway led to a second floor and a half dozen closed doors.

Rosa approached the two intruders. She was a big woman who had seen better days and nights. One of her eyes was missing, and its lid had puckered shut a long time ago.

“If you’re the law,” Rosa said, puffing on the soggy butt of a cigar, “check with Sheriff Pickens. He’s already been paid.”

“We’re not the law,” said Horn.

“Who are you?” Rosa’s dark tongue reached over her upper lip and licked at an errant splotch of cigar leaf trapped in the stringy strands of her moustache.

“We’re hunters,” Horn replied.

“Well, go hunt someplace else,” Rosa barked. “We’re full up.”

“We’re looking for a man,” said Sieber.

“You’ll find a man, all right,” Rosa cackled.

From behind Horn and Sieber a huge mastodon of a creature—a lascar or Oriental—close to seven feet tall made a grab for both men.

Horn moved faster than Sieber, who was caught in the giant’s grip. Horn slugged the giant across his overhung jaw with all the might he could muster and with no visible effect. Horn picked up a chair and with pantherine grace broke it over the mastodon’s head. The mastodon just grunted.

The señoritas laughed. Rosa cackled. Sieber, still in the giant’s hawser hold, banged his fist into the mastodon’s ribs.

Horn drew his .44 and smashed the barrel as hard as he could across the behemoth’s shaven skull. The giant swayed slightly as a curious look came over his pocked face.

Horn brought the gun barrel down hard on the peeled skull again, this time rupturing the boney surface and causing blood to spew. Still holding Sieber, the giant crashed like a gut-shot buffalo across a table filled with bottles and glasses, bringing Sieber down with him.

“Well, I’ll be dipped in tizwin,” said the naked, handsome, dark-skinned Indian who had appeared at the railing. “If it ain’t Al Sieber and Tom Horn.”

The best-looking whore at Rosa’s emerged naked from a room and stood next to the young Indian, who had hold of a Colt Peacemaker pointed at Horn.

“Yeah, it’s us, Kid,” said Horn. “You can lower your weapon.”

The Apache Kid flashed a quick grin, revealing twin rows of even, salt-white teeth. He was in his mid-twenties. He had blazing black eyes, and wore his hair shorter then the Apache but longer than the white man.

The Kid’s grin grew wider. “What’s a couple of nice fellows like you doing in a place like this?” he laughed.

Two hours later, Tom Horn, Al Sieber, and the Apache Kid lay naked in three large copper tubs. The men were being lathered and rinsed by three smiling señoritas whose wet gossamer garments outlined every upland and valley of their damp, dark skin. Each of the men smoked a cigar and drank from his individual whiskey bottle. In truth, the three weren’t completely naked. Around his neck each wore a thong to which was attached an eagle claw.

The three scouts had worn them for almost seven years.

After a campaign against the great Mimbreño chief Vittoro, Sieber, Horn, and the Apache Kid had escaped into the furnace-hot desert. Sieber had been wounded, and the three scouts were afoot, half starved, parched, and without canteens.

The Kid had spotted a golden eagle high on a crag. With the single shot he had left, Horn brought down the bird. They drank its blood and ate its stringy meat. Then Horn and the Kid carried Sieber to Fort Whipple. Sieber gave them each a claw of the eagle. It was an adoption procedure stronger than any proclamation by a court of law. From then on they were his sons.

“Sibi’s Boys,” was what the white man c

alled them. In Apache, they were “the Claws of the Eagle.”

“What’re you two cloud hunters up to?” The Kid winked at his señorita and looked at Horn and Sieber.

“I been nursing my rheumatism at Bowie,” said Sieber, “and Tom went back to the blanket for the winter.”

“How long you been hibernating here, Kid?” asked Horn between puffs.

“I lost count,” the Kid smiled, and looked at his señorita again.

“What do you use for money?” Horn inquired.

“Sometime back I took three hundred dollars from a couple of dumb white-eyes in a poker game. Thought maybe you two was them. They were so dumb they wouldn’t trade a deuce for three aces.”

“Cold deck?” Horn asked.

“Their deck,” the Kid smiled, “but after a while it warmed up to me.”

“Kid”—Sieber’s eyes squeezed into more serious slits—“me and Tom are gonna wear off the winter fat scouting for General Crook again. Thought you’d want to sign on.”

“Scout for ol’ Gray Wolf? Why would I want to do that, when I’m rolling in…”—the Kid’s eyes rolled around at the scrubbing señoritas—“money?”

“How much of that three hundred you got left?” Horn asked, running his hands through his soap-soaked hair.

“Don’t know.” The Kid shrugged and looked toward Rosa, who was igniting a fresh cigar. “Rosa, what’s my tab?”

Rosa always carried a tally book. She flipped it open and referred to the Kid’s account.

“Including them”—she pointed to Sieber and Horn—“and the damages…two hundred eighty-seven dollars and fifty cents.”

“Well,” shrugged Horn, “you can’t roll very far on twelve dollars and fifty cents.”

“Guess I’m signing on,” the Kid laughed, and reached both hands toward his señorita’s ample breast. “After I spend that twelve dollars and fifty cents!”

Chapter Two

General George Crook tapped an Apache arrow against the map of the Arizona Territory and Mexico that hung on the wall of his spartanly furnished headquarters office at Fort Bowie.

The Range Wolf

The Range Wolf Tom Horn And The Apache Kid

Tom Horn And The Apache Kid The Christmas Trespassers

The Christmas Trespassers Black Noon

Black Noon